'Nosferatu' and the Erotics of Evil

Some want to make 'Nosferatu' out to be a feminist horror about women's sexuality. I'm not sure it's quite that simple.

Hello and welcome to Many Such Cases.

I hope you all had a lovely holiday season. I enjoyed a nice little break from working and writing, but make no mistake — I thought of you all and this newsletter every day. I have a few essays on the horizon, including one on the future of male loneliness, another on contemporary art’s erotic entanglement with cars, and maybe even a set of annual predictions of our sexual culture future. I’d probably be publishing the latter now if I weren’t so struck by the latest film I saw in theaters this weekend: Robert Eggers’ 2024 Nosferatu.

The vampire narrative (and by extension, horror as a genre on the whole) has always reflected sexual anxieties. Not exclusively, of course, but the concept of some ominous Other threatening to suck on the neck of a delicate young woman — I mean, duh. The original Nosferatu from 1922 and the 1897 novel Dracula all follow this same theme. Exploring the themes of sexuality, repression and purity in Gothic literature is so popular a convention in the field that some academics have called it “pointless.” But of course, with a new addition to the canon, there are new things to say.

What has always struck me about these conversations is that they serve for many as some sort of “gotcha.” The vampire is a metaphor for our fear of women’s sexual desires! Male characters wanting to stab Dracula through the heart is a parallel for their wish to control our erotic wiles! These are, again, very mainstream analyses of the genre that I do think are still interesting and fun to discuss. But among contemporary viewers and readers, there is often a conclusion drawn, both explicitly and subtextually, that this all means that the vampire is the one we should be rooting for.

This is not the first time Robert Eggers has received this sort of treatment. I often see his 2015 film The VVitch, in which a teenage girl’s entire family living in exile in rural Massachusetts is killed off by the Devil in goat form until she signs her soul over to him as a witch, interpreted as a “good for her” type film. The idea is that she, Thomasin, has escaped from the oppressive forces of religion, culture and family, her independence and burgeoning sexuality now liberated. Of course, her religion, culture and family do oppress her in various ways — as they do the entire family — and her development into womanhood is considered a threat. This is part of where the “witch” concept historically originates. But even so, it is not her family, religion or culture that is the enemy to be destroyed in Eggers’ vision. In Eggers’ world, the Devil is real, he is evil, and he consorts with witches who kidnap infants and use their entrails for flying ointments. By the end of the film, Thomasin has become one such witch, herself. She was not evil from the start, but was made so. Evil here is a concrete force.

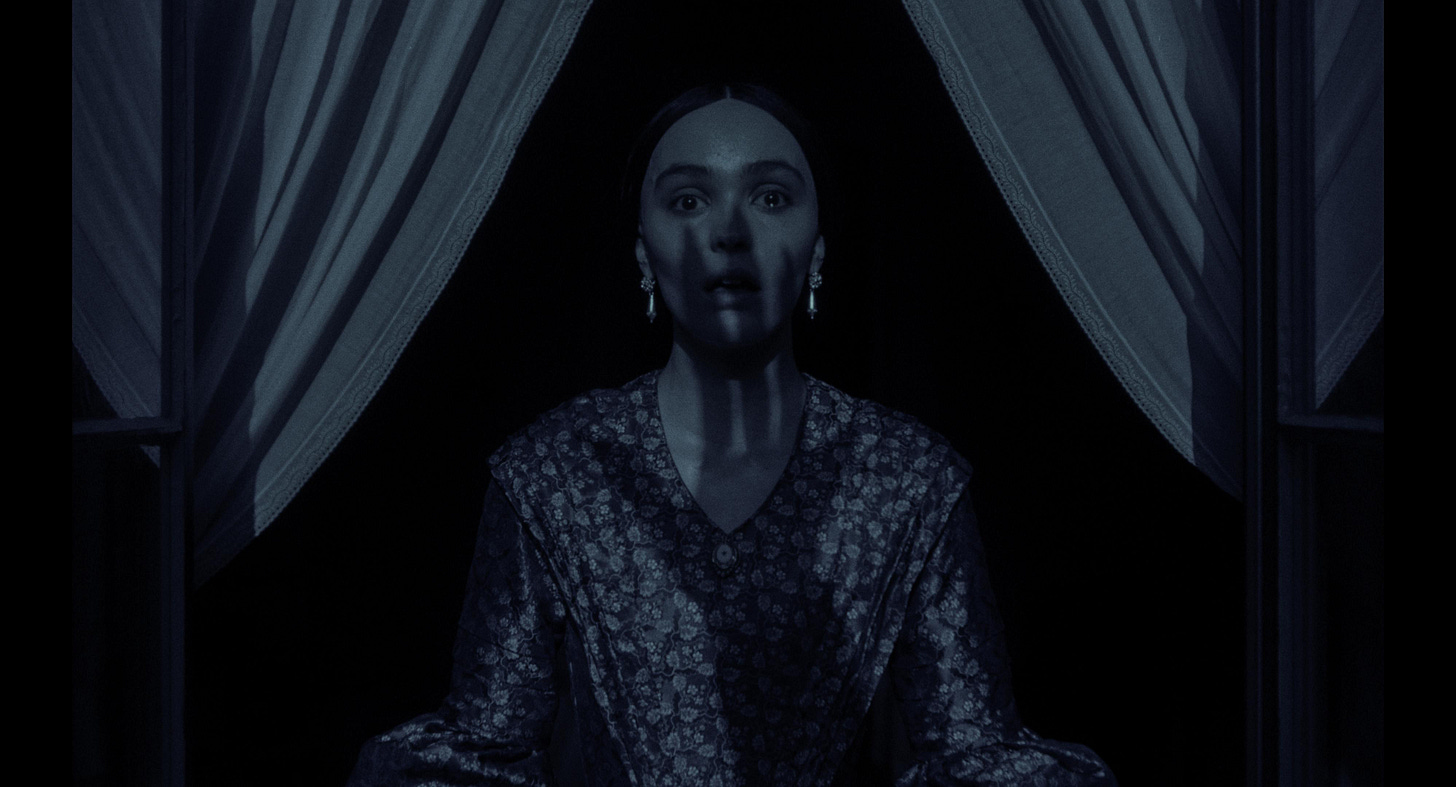

In Nosferatu, our protagonist Ellen (played beautifully by Lily-Rose Depp) faces similar struggles in 1830s Germany. She is a lonely, melancholic young woman; the men in her life know little of what to do with her. One night, in the despair of her solitude, she makes a call out to the universe seeking some sort of angel to offer her comfort. Instead, she awakens Nosferatu, who clings to her soul in a destructive, erotic obsession. Nosferatu, or Count Orlok, tortures Ellen. In her sleep, she experiences nightmares so powerful she thrashes and seizes. Yet, as she enters adulthood and marries, she feels protected by the love of her husband Thomas. She looks at her relationship with Orlok as her biggest “shame.” She wants peace, normalcy, to be freed of the torment. She wants her husband. One can also interpret her as wanting Nosferatu, too, sharing in his sexual obsession. This is part of her sense of shame. But even as she may hold this desire, she begs to be rid of it.

As Nosferatu’s grip on her tightens, her condition worsens. Her husband in Transylvania being similarly tortured by Count Orlok, she stays with a childhood friend Anna, her husband Friedrich and their two children. Under the guidance of a doctor, this husband puts Ellen in a corset and ties her to the bed as she sleeps. Too much blood, they say. We must control the womb, they say. The message here is indeed that they are frightened not just of Ellen, but of her sexuality and womanhood. They are also, of course, frightened by the fact that she is screaming and convulsing in her sleep and speaking of the arrival of some ominous man.

As with Thomasin in The VVitch, I have seen some argue that it is somehow “the patriarchy” who is the true villain here, using these scenes as an example. Ellen’s friend catches the plague — brought to town by Orlok — and is later killed by him along with her two young daughters. Prior to her death, as her symptoms grow worse, Anna tells Ellen that she does not know herself. As one TikTok critic L.P. Longmire suggested, this is Anna admitting that she has never made her own decisions regarding her life, that she has merely gone along with what society and her husband expected of her. Friedrich, in Longmire’s view, is the embodiment of the cultural demands put upon women — “a real life vampire,” he says. Anna had no choice but to be a doormat, living under the foot of a wealthy man with an estate and power who wants to use women for his own gain, just as Orlok does to Ellen. Ellen’s outbursts, according to Longmire, are metaphors for how men see women when we finally stand up for ourselves.

Say that is what Eggers intended these scenes to represent. In the end, Friedrich suffers for it all: he dies (presumably of the plague?) in his pregnant wife’s coffin beside those of his two daughters. So maybe by Longmire’s view, he had it all coming. Or maybe, his real sin was his inability to recognize the force of evil for what it was and acknowledge how it could destroy his family. His crime, as is nearly everyone else’s in the film, is naiveté.

I do not see evidence to suggest that either Ellen or Anna were unhappy with their general lot in life as married women. Ellen, in particular, was clearly in love with her husband. He desires her, he seeks to understand her, he acknowledges the torment she faces as real. Anna and Friedrich, all around rather under-developed characters, were portrayed as perfectly content. To say that Anna represented the plight of motherhood speaks only to the viewer’s own interpretation of it. The destruction of this entire family is supposed to be a tragedy, a sign of what is to come of Nosferatu is not killed. And yet, there are those who see the institution of family as the true villain. Nosferatu’s entrance into Ellen’s life is connected to the family, too. She explains to Professor Albin Eberhart von Franz that she first called to him following the death of her mother, her father having become emotionally absent. Orlok took advantage of her loneliness, her innocence. It is in the absence of family that she became his prey. She is not some horny young woman oppressed by society’s unwillingness to let her indulge in sex: she is a victim to a predator who has been stalking her since childhood.

This story is of course allegorical. Nosferatu may well be a metaphor for the erotic, for the broad specter of the Other. He may represent Ellen’s shame, perhaps strictly over her sexuality and womanhood or maybe something else. His enemy may well be tradition, family, society writ large. But even if it is society that is producing this conflict within Ellen, it does not mean we are supposed to want Orlok to win. Like the goat Devil in The VVitch, he represents evil. Surely, our culture identifies evil in various forms. Horror is as a genre is a reflection of these nuances. In Eggers’ films, however, evil is something concrete. It is a force unto itself, even if only in allegory. The danger of this evil is that it is so easy to welcome in: it is alluring, it can trick us in its sensuality and familiarity. Neither the family nor the erotic are themselves the source of evil. Rather, they are both easily victim and vector to it.

I had expected Nosferatu to be an overall sexier film. Nearly everyone in the primary cast was sexy themselves, but I expected perversion. Depravity. Sexual disruption. All the reviews and memes about its freakiness and wanting to fuck Count Orlok (even from the New York Times!) suggested as much. Instead, I found it overwhelmingly romantic and tragic. I was moved by Ellen and Thomas’s love for each other, their clear passion and desire. It was a film about devotion, not strictly between Orlok and his victim but between genuine lovers. In the end, Ellen’s death is not her succumbing to her desire for Orlok and his power over her but is her own sacrifice for Thomas and the rest of humanity. It is a film that ultimately upholds a belief in a rigid moral compass. Our direction may waver, but a true north exists. At least in the world Eggers depicts.

Just as Lily-Rose Depp’s performance in The Idol highlighted, our relationship with the erotic remains fractured. It is a source of discomfort. And as her role in Nosferatu documented once more, it carries a sense of dread and anxiety. We can be sexually traumatized and empowered all at once. We can hold an honest love and still be haunted by desire. It’s natural that viewers would want some sense of psychological restoration for these rifts, either by explaining away the film as a broader metaphor for bad men or by meme-ing it into sexual submission in labelling Orlok and Ellen as true lovers. By my measure, it was about something far more frightening. Nosferatu tells us that good and evil do exist, and to our horror, the erotic cannot easily be defined within them.

As Persephone is consumed by Pluto in the underworld each winter solstice, so is this movie released.

She is forced to walk in the material world of "death" and "hell on earth" until she goes into her dreams for the other half of the day (the Gods compromised with Pluto to have her released from the underworld half of the time), where she is able to nourish her soul and become reborn in the spring of sleep.

That's my esoteric interpretation of the movie (:

Thanks for embracing the dark, so we may yet find the light Magdalene.

Nailed it. I’ve been reading reviews all day after a great showing and I’m really impressed with your analysis. It really reflects all the cues and choices I felt I got from Eggers throughout the film, as well as fitting hand in glove with my own knowledge of the world.