It's Obviously the Phones

When it comes to loneliness, the decline in sex and our increasingly depressed culture, phones are an obvious culprit. What good is it to deny that?

A year ago, I published an opinion essay for the New York Times that changed the trajectory of my career. It was about how fewer Americans are having sex, across nearly every demographic. For any of the usual caveats — wealth, age, orientation —the data almost always highlighted that previous generations in the same circumstances were having more sex than we are today. My purpose in writing the essay was mainly to try to emphasize the role that sex plays in our cultural wellbeing its connection to the loneliness epidemic. Many of us have developed a blasé attitude toward sex, and I wanted people to care. It wasn’t really about intercourse, and I said as much. It was about wanting to live in an lively, energetic society.

Since writing, I have been continuously asked what I think the cause of all this is. Obviously, there isn’t one universal answer. After publishing, I went on radio shows and podcasts and was asked to share what I thought some of them could be. Economic despair, political unrest, even climate fears were among the reasons I’d heard cited. But all of that, honestly, feels pointlessly abstract. It puts the problem entirely out of our hands, when in fact I believe it may quite literally be in them.

The problem is obviously our phones.

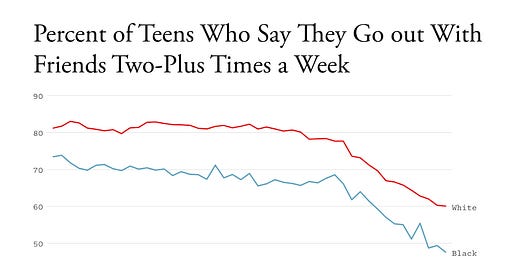

In February, The Atlantic published a feature about the decline of hanging out. Within it was a particularly damning graph sharing the percentage of teens who report hanging out with friends two or more times per week since 1976. Rates were steady around 80 percent up until the mid-90s, when a subtle decrease began to occur. Then, in 2008 — one year after the release of the first iPhone — the decrease became much more dramatic. It has continued falling sharply since, hovering now at just under 60 percent of teens who spend ample time with friends each week.

Some of us really don’t like our screen time habits criticized. Others may think they appear smarter by highlighting other issues, that they can see above the fray and observe the macro trends that are really shaping our lives, not that stupid anti-phone rhetoric we hear from the Boomers. And some of these other trends do indeed apply. Correlation does not equal causation. Lots of things happened in 2008. Namely, a financial crisis the effects of which many argue we are still experiencing. When I shared the graph on Twitter/X saying phones are the obvious cause, this was one of the most common rebuttals. Another was the decline in third spaces. There are indeed few places for teenagers to hang out outside of the home. Skate parks are being turned into pickleball courts with “no loitering” signs, malls are shuttering and you can no longer spend $1 on a McChicken to justify hanging out in the McDonald’s dining area for hours. But as the Atlantic piece explains, the dwindling of places to be and experience community has a problem we’ve been lamenting since the 90s. And it’s not just teens — everyone is spending less time together than they used to. “In short, there is no statistical record of any other period in U.S. history when people have spent more time on their own,” the article states.

The fact remains that even with the financial crisis, even with the lack of third spaces, we could all still be experiencing the company of our friends and family at home for free, and we are choosing not to. The U.S. Census Bureau’s American Time Use survey shows that we’re even spending less time with our spouses and children in favor of being alone. It’s because we’re on our phones, instead.

Americans average around four and a half hours per day on their phones, with some of us averaging much higher. There are plenty of people looking at their phones upwards of ten hours per day. I personally average in at six and a half hours daily, and I hate it. Much of this time is spent on social media, which I justify as an extension of my work, but the reality is that I am addicted to scrolling and receiving notifications. I recently implemented a time limit on certain apps, which is partially helping.

Maybe we want to say social media or the Internet are the real culprits here, but when we talk about phone usage this is exactly what we’re talking about. Smart phones have allowed us to have constant access to social media and the rest of what the Internet offers — including porn — and is now the dominant form through which we do so. There’s an asinine XKCD comic strip people love to cite detailing how every new form of media consumption throughout history has been blamed for the end of socialization. Books, newspapers, television, walkmans have all been cited as reasons why people don’t talk to each other anymore. And yes, maybe the phenomenon of people talking to strangers in public has been dying for hundreds of years now, but there remains something entirely contemporary about what phones are doing to us now.

People were not collectively spending up to ten hours every single day reading. They were not habitually choosing books over real people en masse. Even when people did begin spending hours every day on television and video games, the broader trends in time spent with others did not drastically shift. In 1950, the typical American household already watched four and a half hours of TV per day. People have been consuming copious quantities of media for decades now, but it wasn’t until the smart phone, a device we carry with us at nearly every moment, that we began to be so alone. Neither books nor television simulate socialization in the way our phones do.

Of course, the iPhone is not the only thing marking the difference between the 1950s and today, or even the early 2000s and today. You’re right to think life is economically harder, that there are fewer ways to form a community, that there are countless global issues to feel depressed about. I’m not going to act like deaths of despair like opioid overdoses have risen because we’re on our phones too much. But the reality is that some of these changes, and more importantly how we perceive them, are phone-informed. You’re aware of how bad life is because your phone is constantly telling you about it.

All but one of the top seven largest companies in the world by market cap are tech giants (Microsoft, Apple, NVIDIA, Amazon, Google and Meta), the exception being petroleum company Saudi Aramco. I don’t know much about economics, but I’d venture to guess that there is some financial incentive for these companies to keep you on your devices as long as possible. The decline in third spaces and places to form real-life community is tied to these economic conditions, too.

Many people on Twitter/X shared images from local parks with “no ball throwing” and other no-loitering-esque signs actively deterring children and teens from enjoying the space. People have every right to be angry about these cases, that there are few places to simply be. But even these situations can be traced in part to our phone-centric culture. Say these are some sort of small town governmental decision — because of our current tech landscape, we no longer have strong local news infrastructures to help inform locals of these types of moves. And because we have our phones and other screens to fall back upon, we’re unlikely to really take much time to attend the city council or Town Hall meetings that allow us as citizens to change these matters, anyway.

That is completely understandable. People are exhausted, they have jobs, they have families. You shouldn’t have to fight for places to be, for things to do offline. At the present moment, we’re stuck. We don’t know how to make friends or date or follow the news or even buy clothing without the help of our phones, and none of it is really our fault. Even as I complain about it, it’s not as though I’m going to give mine up entirely. What I really want for myself and everyone else is to just use my phone less. That is something we are in control of. I want people to prioritize the real world. Sex, the heart of what I most often write about, is one component of that. I care about sex and care about people having it because it’s something real. When I encouraged people to “have more sex” in the Times essay, that is ultimately what I was calling for: a renewed emphasis on the real.

De-centering phones is another real thing we can do to better our social lives. The economy is out of our control, but our own personal tech consumption isn’t. We will get nowhere by defending the phones. At very least, we’re not going to bring back book clubs and bowling leagues by watching YouTube videos and swiping on Tinder. There aren’t going to be spaces to exist and meet if people would rather stay home and scroll. A better world is not going to be built by increasing our screen time.

The "people have said this about all media in the past" stuff bothers me because unique among all of them the Smart Phone made it easier to access social media and make a virtual reconstruction of "hanging out". Reading a book does not simulate the experience of having a conversation with a group of friends, nor does TV really. The phone does.

The screens ensured that day and night, people hear about “statistics proving that people today had more food, more clothes, better houses, better recreations—that they lived longer, worked shorter hours, were bigger, healthier, stronger, happier, more intelligent, better educated, than the people of fifty years ago.” - This was something that I read from a 1984 book analysis on the telescreen. I’ve been saying since 2018 ish, something is off. Perhaps it’s been longer, maybe it was more subtle I just didn’t acknowledge. The kids aren’t all right…