"Just A Chill Guy" Is The Only Thing Men Are Allowed to Be

Desire Digest 006: The "chill guy" meme, Wifejaks and mistaking the Manosphere

Hello and welcome to Many Such Cases.

I’ve been firing off essay after essay on here with more to come, and it has been paying off. I am learning, for better or worse, that conversations about the animosity between genders right now are resonating with people most. I hadn’t even planned at all to time the Do Men/Women Even Like Each Other Anymore essays around the election, but thank God that I happened to do so. There will be more on these themes to come.

I recently hit 10,000 subscribers (I’m actually already over 11k now!) and each day I inch closer to achieving my dream of forming a solid income on here. This Thanksgiving, I am thankful for you all. I will of course use this as an opportunity to once again encourage you to become a paid subscriber so I can continue to write and dissect what is happening in our sexual culture and the frontlines of the Gender War and also pay rent. I love you.

Anyways, here are some smaller topics that have been on my mind this week. A lot of it is meme related, which can at times feel superficial. This itself is worth interrogating, though — so much of our current capacity to express ourselves, our relationships and our sexuality is exclusively relegated to memes. It saves us from being overly sincere. That’s okay. I’m going to keep writing about all of it, regardless.

“I’m Just a Chill Guy”

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

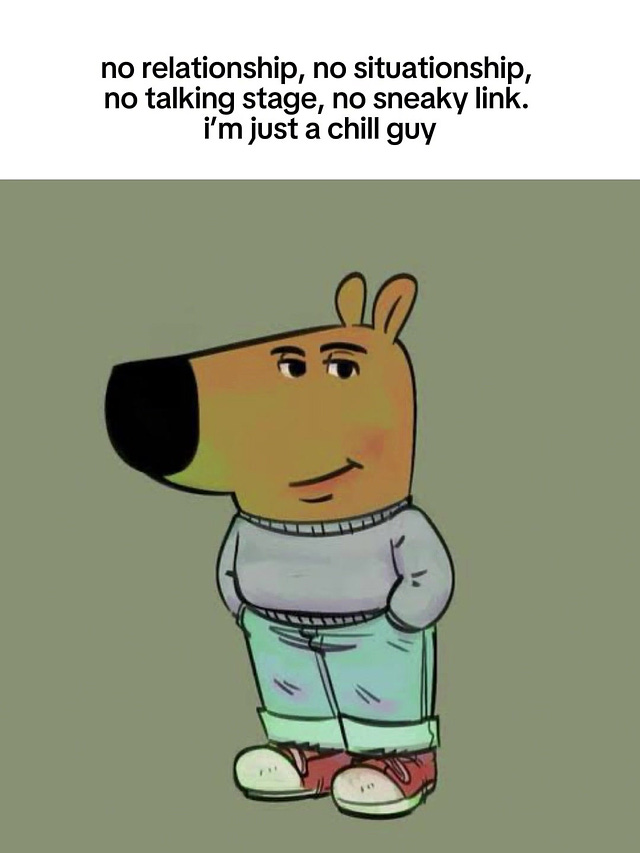

Imagine if you had a simple way of representing yourself as a laid-back dude with few concerns or obligations. Imagine you were a man who said “no worries” and meant it. Imagine you were just a chill guy. Such is the essence of the meme currently circulating, which features a half-smiling dog cartoon character wearing a sweater and jeans with his hands in his pockets. He’s come to depict how men would like to be perceived in a variety of situations, particularly as it relates to their social and romantic lives: “no relationship, no situationship, no talking stage, no sneaky link. i’m just a chill guy,” one reads.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Being “just a chill guy” serves several functions. There are some cases in which it comes from a position of superiority, wherein everyone expects you to have some sort of emotional response but you’re so chill that you’re above it all. Underneath this, though, it protects us from the consequences of both seeing ourselves and being seen as neurotic, complicated people. Nobody wants you to be anything but a chill guy, and certainly, you shouldn’t disappoint them. “Just a chill guy” is a complete non-threat, an identity served entirely by its emotional emptiness. We’re uncomfortable with men expressing themselves in any other way, and this meme demonstrates our complete resignation with that reality. Particularly when it comes to sex and dating, being “just a chill guy” takes away any sense of desperation, though this itself is a tell. The chill guy is a passive participant. He represents our current sense of the lack of authority in our own lives, and the imperative to grin and bear it, anyway.

At the same time, isn’t being a chill guy something of a relief? Isn’t it easier this way? How else are we supposed to be? The chill guy wouldn’t overthink it, and neither should I.

The Optimism of the Wifejak

I know many of you would say that as a woman, I am incapable of understanding what the Wifejak meme means. I’m not even a wife yet! But I nevertheless enjoy seeing how other people navigate the format. It tells us a lot about how little we understand each other as men and women despite many of our attempts in earnest and also how that is probably fine.

The prevalence of the meme also asserts my belief I’ve repeated before that most people want things to be normal. They want normal things like relationships, marriage and a family. They want to poke fun at their wife’s desire to only get dessert if they’re going to get it too or why she put the Christmas decorations up so early this year. It’s the same wifeguy humor we’ve seen for the last decade. Some have been arguing that it’s a complete turn from the “I hate my wife” style of comedy, though I generally think both are coming from the same place of being annoyed with one’s partner but largely still wanting to be with them.

The only people who hate the Wifejak meme are guys like Nick Fuentes, who thinks being a wife guy is “gay.” In his livestream back in April when the meme first started circulating, a viewer sent Fuentes $100 and the message “That stupid Wifejak meme has turned Twitter into a total coal factory. Everyone is outing themselves as little pussy whipped bitches. Please Nick come back soon and lead the incel jihad to cleanse the timeline.”

I don’t think it requires much elaborating: these people are not normal. They do not represent the way most people feel. Instead, most people would rather make fun of their partner’s behaviors and still love them. They also want to embrace the universality of that experience with other normal people.

Mistaking the Manosphere

This latter point is a good introduction to a topic I saw

emphasize this week, that there appears to be some mainstream conflation between the Manosphere and the rest of men’s-centric, bro-y media. While both may have contributed to the election result, the two are not the same and it’s a mistake to believe they both represent the attitudes of young men today. The Manosphere refers specifically to a universe of men’s groups that center around misogyny, men’s rights and inceldom. The bro media circuit, which writer has named “the Zynternet” thanks to this group’s affinity for Zyn nicotine pouches, are essentially just bros. Sure, there’s overlap, and some of these online bro’s are indeed misogynistic. But to say that the Zynternet is the same as the Manosphere, that all these guys who listen to podcasts and follow Barstool Sports hate women and want them to lose their rights is a complete misidentification, and one that I think is part of why the Dems lost. I spoke a bit about this on NPR’s It’s Been a Minute back in July, but one of the big cultural problems of the Left is how so much of masculinity has been labelled as conservative and therefore bad. Beer-drinking and sports, for example, are seen as Right-wing coded interests when in fact they are largely non-political activities that anyone can enjoy. But when you start to vilify these everyday, fun things as conservative, you are actually only going to start pushing the people who want to feel free to enjoy them further to the Right.I wanted to bring this up here as someone who does write about masculinity and the Manosphere, because I do think it’s important to define my terms. When I talk about the Manosphere, I am talking about incels and men who vocally, avowedly hate women. As much as the discourse around these things has been twisted lately, this does not accurately describe the average online bro or even the average young Trump voter. Even if we fundamentally disagree with these groups, the only way we’re going to get anywhere is if we at least try to understand each other a little better.

It's nice to see someone objectively recognize that the seething Nick Fuentes/Andrew Tate incel corner of the manosphere is a fringe one, largely disconnected from the mainstream bros who enjoy a cold one and bitching about why the Browns will never get it together.

The latter generally love their wives and girlfriends and moms and sisters and will go to the mat for them, regardless of how their idiosyncracies grate on their nerves. The former will die angry and lonely, some in the headlines, some in obscurity.

I am conservative in how I think the government should be run (a smaller government that is fiscally responsible and doesn't deficit-spend) but very liberal regarding social policies. I am also a very sensitive person and am becoming more comfortable expressing that I am a bisexual man. But I am also very masculine and straight-acting and looking. I have worked blue-collar jobs in the past and have associated with many who could be considered "bros," along with a lot of misogynistic people. I have lost count of the number of times I listened to people express opinions that were an attack against me, even though they had no idea they were attacking me because I hid my authentic self. I have also listened to and watched a lot of the influencers in the manosphere and conservative media. Like most things in our society, it seems people can make a living creating polarity, which is really sad. Over the last several months, I have distanced myself from a lot of the manosphere and conservative media because it doesn't resonate with me. And neither does leftist media, which is equally polarizing. Trying to put people in Box A or Box B leaves a lot of the nuance of humans on the table.

I also deal with women I like and respect very much who say some truly hateful things about men. Unfortunately, I need to stay quiet about my beliefs in those situations or risk losing a friend. Most of our landscape between genders is a mess, and it is unfortunate. There also seems to be a "contest" to see who's pain is more valid. I can say from first-hand experience that navigating life as a bisexual man is not easy, but in many cases, women that I consider friends want to tell me how much harder women have it. Or transgender people or people of color. Why can't I share my experience and troubles navigating life without my issues being brushed off in comparison to someone else? Can't both things be true at the same time? As someone who lives with many opposing views, which are valid for me, without each view supporting the other, I find our current environment difficult.

I understand why men would like to adopt the "Chill Guy" persona, but for me, that isn't anywhere close to my reality. However, there are many situations where that is precisely how I need to behave, and that can cause a tremendous amount of stress and anxiety. Ultimately, being the "Chill Guy" leaves me feeling alone, isolated, and unheard. I find many of the "influencers" on both sides of the coin as merely content creators that are unable to see the nuance between indivduals.